When does the workforce like automation? ..

.. or dislike it

About a year ago, at one of the many networking events in Berlin, I met a very sympathetic company CEO with whom we had an interesting conversation regarding robotics and automation.

He stated that due to robotics and automation, they had a productive increase of about 10x for the last 20 years. As that is quite an impressive number, so I got curious about what the workforce in the company thinks about these impressive productivity gains since we usually think that productivity gains have layoffs as a consequence.

To my surprise, he answered that during the same time period, the company also increased its workforce by over 5x. That came as a surprise or even a paradox but he explained further if not for the automation gains, the quantity of people that they would have to hire to cope with the growth in demand is simply not available in the German labor market. Therefore, automation is not a nice-to-have to improve profits; automation is a must-have to serve the accumulated customer demand.

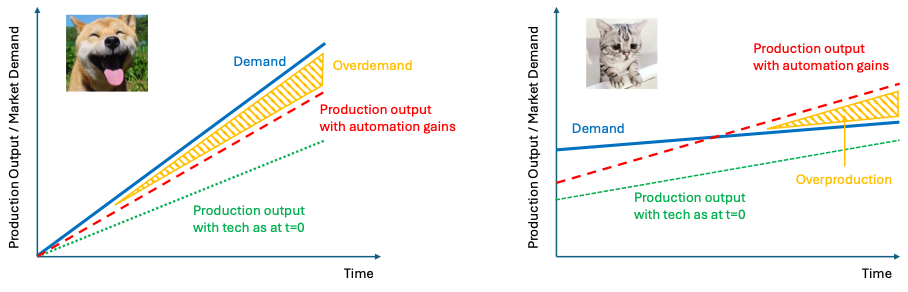

For me, this little anecdote contains a very insightful lesson about the relationship between automation and growth and companies' workforce. Look at the figurative graphs below.

In both graphs the blue line represents the market demand over time, the green dotted line represents the product output over time if the production technology is untouched as in the beginning, and the red dashed line represents the production output if automation allows to increase the workforce productivity.

On the left-hand side, the scenario is shown as described by the anecdote above: Market growth is so strong, that even automation gains do not allow cope to satisfy the market fully. Here the yellowish area represents an overdemand. In this case, the workforce is happy about automation improvements as (1) they can usually do less repetitive stuff and cooler tasks, (2) working hours are reduced without substantial salary decreases as otherwise, the employer would lose market share since less productive hours means less productive outputs, (3) higher end-of-year bonuses due to higher revenues (and for those who have virtual and real shares, the value of the shares goes up).

On the right-hand side, the scenario of a saturated or slow-growing market is shown: In this case, automation gains will lead to overproduction. As overproduction means lower prices, companies will try to avoid this scenario and rather reduce production capacities usually by reducing the workforce. This is obviously, a scenario that people in the workforce are not happy about and which is usually connected to the fear of automation by AI and robotics making people obsolete.

As we see, the question depends not only on the automation gains that we can achieve but also on the market growth in a particular segment. As many of us work in markets that are either “naturally” saturated (an average person cannot eat or probably should not more than 3000 calories a day) or “artificially” saturated (people can’t buy more goods or services than they have income), we take the idea of “saturated markets” as a given.

In this context, the topic of software engineering, is a particularly interesting market to look at, as LLM seems to provide extraordinarily high productive gains in this area. People claimed that using tools like Copilot or lately ChatGPT had productivity gains of around 20 % while the demand for software engineering seems to grow at the same right. Thus, in the short and mid-term, I would expect that we will just see more and more software being released rather a sharp shortage of jobs in software engineering. In the mid-to-long term, I would still expect the productivity gains to compound such, that automation gains will outperform market growth.

What will be still relevant then if software engineering becomes basically a commodity? Market access. It might seem like winding back the wheel of time but I would expect that a strong brand and distribution network will become more important than it has been for the last 15 years.

In an ideal world, we should automate everything we can to free up the time of people to take care of stuff that can’t or rather shouldn’t be automated. In the real world, it is one of the most challenging issues of our time to find out how the huge automation gains that we are about to experience can be redistributed in such a way that we can approximate the ideal world scenario as well as possible.

Meanwhile, the causalities mentioned above hold an important lesson for each individual who is entering the job market or is looking for a new job right now: It may seem that analyzing markets and market opportunities is something for quants at investment banks but it is just as important for you as an individual to be conscious about which industry you want to enter and have an idea if it a growing, saturated or even declining one. You are investing your (yet) most valuable resource: Time. You can find almost any kind of position, in any kind of industry. But depending on which industry you enter and invest your time in, the return on investment might look very different.